Accessible animated GIFs are pointless

Posted 8th January 2021 in Accessibility

Animated GIFs (or video files that behave just like animated GIFs) are everywhere you look: from social media and messaging services, to email and even on websites. So how do we use them accessibly? I’m afraid to say, the most accessible way to use animated GIFs is probably not to use them at all.

Let’s start with what people expect of an animated GIF:

- They start animating automatically

- They only last a few of seconds

- They repeat infinitely

This simplicity, immediacy and repetition is part of their popularity; we can reply to someone’s message with a funny looping clip from our favourite film, or illustrate a point with a cute snippet from a cartoon series from our youth.

But the reasons for their appeal are also why they cause accessibility issues, failing the very minimum level of accessibility conformance (level A) as they don’t meet the Pause, Stop, Hide success criterion, which says:

For any moving, blinking or scrolling information that (1) starts automatically, (2) lasts more than five seconds, and (3) is presented in parallel with other content, there is a mechanism for the user to pause, stop, or hide it

To meet this standard an animated GIF must:

- start automatically, as long as the animation lasts five seconds or less

- start automatically and loop, but total no more than five seconds

- start automatically and loop indefinitely, but have a way to pause, stop or hide it

- not start automatically, instead providing a button to start the animation; but when it does start, it can loop indefinitely

Nobody’s going to go with the first two; stopping inside 5 seconds defeats the object of an animated GIF, and might mean the message is missed if the reader isn’t paying close attention.

The third method, where the video plays automatically but can be paused/stopped or hidden, is probably the easiest to achieve, but can have its own usability—as well as accessibility—pitfalls. For example, Slack for macOS has a downward-pointing triangular arrow icon just above the image that, when clicked, hides the GIF and points to the right; when clicked again it shows the GIF and points down again. But:

- Is that arrow obvious enough to the user?

- Is it clear enough what the arrow does?

- Is the arrow a big enough target to be clicked/tapped easily?

- If the user has an issue with motion, are they able to spot it and click it within five seconds?

- How does a speech recognition user trigger it?

The fourth solution is, to me, the most accessible. Nothing animates until the user asks for it to. I’d combine this with number 3 and offer controls to stop/pause/hide the animation, once it starts. An app that does this is Twitter, but unfortunately it’s not the default, and has to be activated by the user (Settings and privacy → Accessibility → Video autoplay → Never).

Some other considerations

As ever, it’s not as simple as just picking one of those four options; there are other downsides to animated GIFs that should be carefully negotiated.

Auto-start might have already finished

As I mentioned above, if the animation stops within 5 seconds, and the user misses part or all of it, they have to refresh the page to view it again.

It’s likely the image will have loaded in before it comes into the viewport, so may have already played out before the user reaches it. This can be helped to some extent by using the loading="lazy" attribute, but there’s still a risk that the user scrolls down just enough to trigger the fetch, only to stop scrolling or idly scroll back up slightly and move it fully or partially back out of the viewport.

Use alt text

Be sure to add a text alternative to the GIF so that screen reader users (and search engines) know what message it’s conveying.

This is pretty straightforward if you’re in charge of the code and can add alt="" text, describing the contents of the animated GIF, but with third party platforms like Slack, for example, your GIFs you add may fail to meet the Audio-only and Video-only (Prerecorded) success criterion:

Either an alternative for time-based media or an audio track is provided that presents equivalent information for prerecorded video-only content

(Animated GIFs arguably fall under Non-text Content, not satisfying text alternatives at least provide descriptive identification of the non-text content

, but it amounts to the same thing)

To pick on Twitter again, they do a reasonable job here, overlaying an uploaded image with a slightly cryptic “+ALT” button. Changing this button’s label to something like “Add description” would be much clearer, but I’d like to see them go one step further and present a dialog asking the user to describe the image they’ve just uploaded. It’d add friction to uploading media, but it would mean non sighted users would know what the image was.

Careful with flashing images

If we’re going to use an animated GIF, we should be sure than we meet the ‘Three Flashes or Below Threshold’ success criterion so that:

Web pages do not contain anything that flashes more than three times in any one second period, or the flash is below the general flash and red flash thresholds

Very important to adhere to this, or we risk inducing seizures in some users.

Keep things slim line

Let’s not forget file size! Animated GIFs can be pretty huge, so we need to ensure they don’t take the page weight past our agreed performance budget.

Luckily, the MP4 video format can be embedded in the <picture> element, which means we get a much more efficient compression. Still: keep an eye on it!

Respect your user’s preferences

Something else to keep in mind is that we can respect our users’ preferences by serving the animated GIF to the user if they haven’t turned their operation system’s ‘Reduce motion’ setting on.

That way the only users who will see the animation are those who both:

- Have an operating system that supports the

prefers-reduced-motionAPI - Don’t have ‘Reduce motion’ switched on

For users who don’t qualify for the above enhancement, a static alternative image should be provided that clearly conveys the same message as the animated GIF.

Is it really worth all the bother?

Here’s a thought: if we’re adding animated GIFs to our website with a static fall-back image that conveys exactly the same message, why don’t we just use the static image and ditch the animation? Wouldn’t that be the best approach for our email communications, message chat and social media posts too?

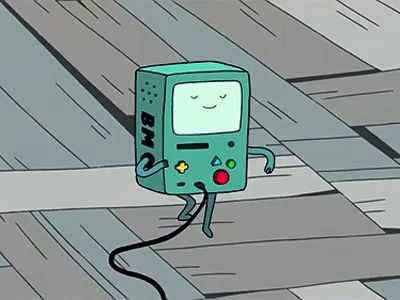

Here’s an example; first up an animation. I’ve used an MP4 and the <video> element rather than an animated GIF as an <img> or in a <picture> element because:

- The MP4 file size I got is over five times smaller than the equivalent GIF (36KB versus 196KB!)

- The user has control of when it starts by clicking/tapping anywhere on the video, including the play button

- The

loopattribute repeats the animation until the user clicks/taps anywhere on the video, including the pause button - The

titleattribute gives the<video>element an accessible name for screen readers

Using the native <video> element isn’t without its pitfalls, but for the purpose I’ve used here it should stand up well:

And here’s an image that conveys exactly the same meaning and even energy as the animated version:

With a plain old JPEG, PNG or WebP, we don’t have to worry about the five second rule, the play/pause issues, and the file size issues pale in comparison. Sure, it’s a bit less fun for some users, but I’m always happy to make ‘compromises’ if it means including everyone!